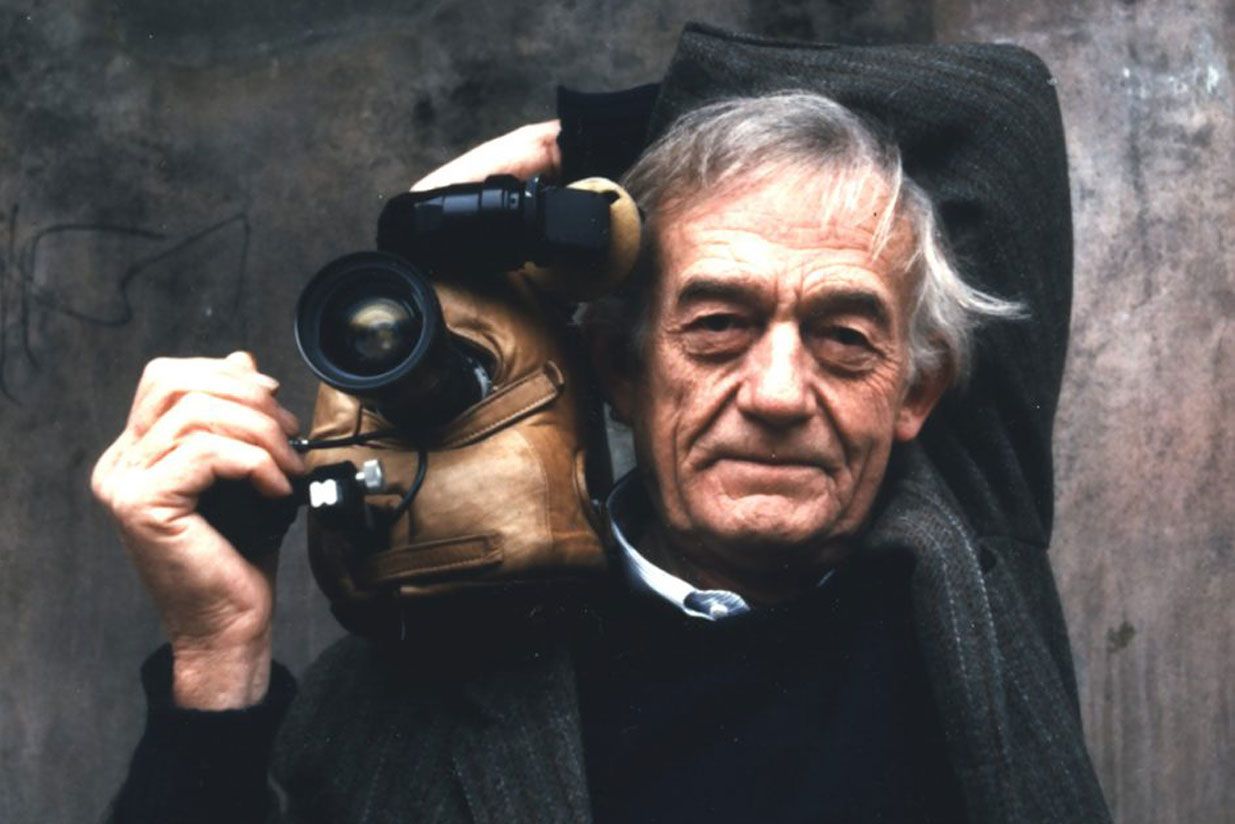

Richard Leacock, «the feeling of being there»

The scene must have been something like what follows. An English boarding school in the thirties of the twentieth century. The boys meet up to play cricket, study Shakespeare, just to chat or to play a dirty trick on somebody, the kind of things boys are meant to do when they are in an English boarding school and they are between eight and fourteen years old. One of them is Richard Leacock, who was born right there, in London, the 18th July 1921, but who lived in Gran Canaria until he was eight, in Guia specifically; where his father owned a banana plantation. His colleagues at the boarding school must have been very interested on knowing what those Canary Islands were like, where he used to live. And he must have run out of words or maybe he had too many, quite useless surely, because what Leacock wanted was not only to explain, but to carry them to the Islands, «…where I came from and what life in my Garden of Eden was like?». So in 1935 he made a decision under a promise that would accompany him for the rest of his life: he’d film it and allow his classmates to have the feeling of being there.

Canary Bananas

Three years earlier, little Richard Leacock had watched the feature documentary Turksib (1929), directed by Victor Turin, one of the documentary pioneers in the Soviet Union, about the construction of the trans siberian train. And it was after this experience when he set up his will and determination to make movies, and the conviction that «I only need a camera and I can make a movie that will make you feel like you are there». So on the summer holidays of 1935 he went visit his parents in Guia, wrote a script and drew the storyboard, and with the help of two of his classmates, Polly Church and Noel Florence, and with a Victor 16mm camera, he filmed it and edited it himself, with the intention of showing it to his colleagues at the boarding school. The movie, Canary Bananas (1935), shows the whole work process at the estate until the bunches of bananas are shipped to Europe. Silent and with a length of ten minutes, it’s a historical document that will end up turning him into a director, but, according to his own words, it didn’t make anyone have the «feeling of being there». It’s fine, he must have thought, this cinema business is fascinating enough to keep trying.

His next cinematic adventure was in 1938, on a different archipelago, the Galapagos Islands, where he arrived as part of the expedition of the naturalist David Lack, with the mission of taking pictures of the same finches Darwin had observed on his journeys a hundred years earlier. According to his own tale, there wasn’t much to do on that isolated and desertic landscape, apart from chatting with the four Angermeyer brothers «who had listened to Hitler and run away» from Germany to establish themselves as colonialists on these islands. So he fulfilled the mission of filming the birds and everything that moved there, an experience he described as interesting and constructive, even though the movie he produced didn’t transmit «the feeling of being there» either.

That school, the Darlington Hall School, right after Bedales School, where he arrived distraught for abandoning his little paradise in the Canary Islands, will be fundamental in his life. Not only because David Lack, who took him to the Galapagos, was his first biology professor, but because it was there where Franny and Monica Flaherty studied, daughters of Robert Flaherty, a pioneer on documentary films, with whom he’ll work on his next big cinematographic project. Leacock says that he met Mr. Flaherty on 1936, barely a year after filming Canary Bananas, on a trip he took with his daughters. In that meeting, and always according to Leacock, Mr. Flaherty set up his tripod and his 16mm camera and just filmed the young and blonde Brenda MacDermont brushing her hair. It all seemed perfectly normal, considering he was the master of documentary observation, but Leacock couldn’t stop observing Flaherty who, at the same time, wouldn’t stop observing Brenda through the visor, filming and filming. What could be so mysterious about a girl brushing her hair to dedicate it so much time and film? «I decided he was mad», Leacock explains, and he wouldn’t understand that madness until he met him again, at the Louisiana Story shooting.

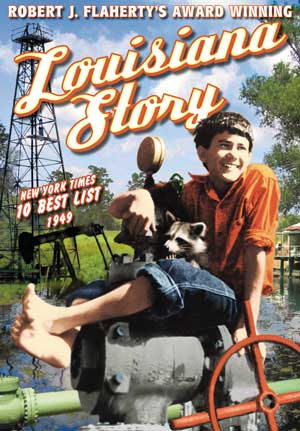

Louisiana Story

Leacock doesn’t speak a lot on his writings about the three years he spent at the front in China and Birmania, working as a camera operator for the War Department of the United States. It was a frustrating experience where he would send rolls and rolls of film to «some unknown place» without being able to see the results of his work, almost ever. When the battles were over he feltl like a war veteran: lost and not able to trust his abilities to be a good film operator.

Before the war he had graduated in Physics at Harvard University, and he had started working as an editor and camera operator on several productions for other directors, but that baggage didn’t seem to be enough. Leacock still insisted on chasing that dream of transmitting «the feeling of being there», and he might have thought he still had a lot to learn, experiment and, specially, shoot, even though he had seen and survived a World War and had been decorated for it.

Years earlier, in 1936, one of his professors, geographist and anthropologist Bill Hunter, had shown Canary Bananas to Mr. Flaherty, who after seeing it said: «…someday we would make a film together». Ten years later that «ex-G.I.s searching for work», as he would define himself, showed up at the chelsea Hotel in New York where, he had been told, Mr. And Mrs Flaherty were staying. To his surprise, the director not only told him about his new project and invited him to participate, but he even didn’t ask to see any of his other works after Canary Bananas, he simply hired him. «This struck me at the time as tantamount to irresponsible behavior», Leacock would mention afterwards, but of course, excited and stunned by that irresponsibility, he accepted the job.

On the springtime of 1947, the production team for Louisiana Story (1948), formed by Mr. and Mrs. Flaherty, the pioneer of documentary editing Helen Van Dongen, Leacock himself – they both appear on the film’s credits also as associated producers – and Robert Flaherty’s secretary, who was with them during the first few months of shooting, when the director was writing the script; they stayed near the city of Abbeville, in the Bayou country, on the bank of the Mississippi river.

The movie, that could fit within the docudrama genre, tells the everyday life of a Cajun family and the worker’s jobs in an oil company drilling one of the wells in their lands. For fourteen months they worked on the shooting of this film, but rather than focusing on the script, «…a location is found, the director tells you where to put the camera and how the camera should move; he then tells the actor(s) what to do, how to move, what to look like. But not Flaherty.», he didn’t give directions on where to put the camera or how to move it, he didn’t direct the actors either. Leacock specifically remembers one of the anecdotes of the shooting, when they were filming the protagonist boy, Joseph C. Boudreaux, looking for hir racoon JoJo. «The tree was there, JoJo was there, a reflector was adjusted. I was ready with the camera when Mr. Flaherty found a spider’s web bejeweled with drops of dew in perfect light. We spent the whole morning filming the cobweb». They filmed «everything that would catch our eye, even if it wasn’t on the script. A nice cloud, some swallows in the sky getting ready to migrate, a drop of water on a lily, perfectly illuminated…». From Flaherty he learnt how to work thinking of the sequence, the complexity of its construction, frame by frame. But especially, during those never ending days of filming, from dawn till dusk, he’d remember that lesson of his visit to the school. There were no rules except to watch, to look through the lens of the camera, and search; in nature, in Louisiana’s or in the blonde hair of a teenage girl’s brushing it. Leacock would consider that shoot as the grandest experience of his life and he’d remember it whenever he had the chance, honouring his great master.

«How to find the main boy? J.C. Boudreaux could be… poor and shoeless but he shined on the screen, he was perfect»

Shoot, shoot and shoot… Jazz Dance

Journalist Richard Brody tells on his article in The New Yorker, In Memoriam: Richard Leacock (2011), that he was invited by the former to make him dinner when he visited him in Paris and to clarify some aspects on the director Jean-Luc Godard, of whom Brody had recently written about and to which Leacock had mentioned: «You know nothing about Godard, you just believe the myth».

And, as a matter of fact, Leacock explained some aspects about the French director that were unknown to the journalist and he then showed him some of his earlier projects, where Jazz Dance (1954) standed out, directed by Roger Tilton. Leacock, beaming by remembering that work, mentioning that at this filming «I fell in love every five minutes». What did Leacock find so interesting about this production? Watch the wonderful final scene, around the 19th minute, with that frenetic and millimetric editing, pure cinema.

«Me? I was all over the place having the time of my life, jumping, dancing shooting right in the midst of everything» «I had nothing to do with the editing but, what a job!»

Counting his previous big project with Flaherty and this new adventure with Tilton, Leacock had participated, filming, editing and even directing and acting – on Head of House (1950) – on five productions, but it was on this project with Tilton with which the camera operator in search of new sensations considered, ironically, he had started the «second step to his de-professionalization».

Tilton wanted to film that project in a small dive in New York, where young people danced to a live jazz band. The “professionals” warned him that would only work out in a controlled stage, «with a clapperboard, take one, take two… », since the so called “portable” equipment for magnetic sound recording weighed 30 kg and the easy to use cameras were the Mitchell NC, noisy and pretty heavy as well. But the tandem Tilton-Leacock didn’t quit on their tenacity to film where the action was. The solution: two cameras like the ones used by the war photographers of the time, two 35mm Eymos, spring-powered that could carry rolls of film of one minute but would only allow you to shoot for fifteen seconds before they needed to be winded-up again, but light and pretty easy to use, which allowed Leacock, while Hugh Bell winded up the cameras, to work while «jumping, dancing, filming in the middle of all the people» and fall in love every five minutes. Bob Cambell, the other operator, shot with another camera the wider frames and the sound was recorded with an old fashioned self-sufficient system that they placed as close to the band as possible. The result, when shown at the theatres, was spectacular, «the sound seemed to be perfectly synchronized with the images» and at last, for the first time in his career, Leacock was able to say «Wow! You had the feeling of being there».

On that same year he signed onto another project that will allow hit to have total control on a production for the first time since Canary Bananas. The film was Toby and the Tall Corn (1954), a report about a theatre company touring around the Mid West. He wrote the script, directed it, filmed it and edited it, like in 1935. The film was important for what it meant for Leacock’s self esteem and, also, because it gave him the chance to meet another director and producer fundamental for his career, Bob Drew, with whom he’d carry on the true cinematic revolution he was looking for.

Robert Drew, here comes the revolution

Robert Drew was one of those guys whose lives could have been a movie. Like Leacock, he fought during the World War, as a bomber pilot, and he met there the famous war reporter Ernie Pyle, who will influence on his later career behind the cameras. After surviving for three months behind enemy lines and once he was safe, he was sent home where he wrote an article for Life Magazine in his experience as a pilot of warplanes. The firm hired him as a collaborator and later as a corresponsal and editor, and received a scholarship from Harvard University where Drew would focus on a specific aspect that would change the course of modern documentarism. The question he asked himself was: why are documentaries so boring? And he started working on making them more attractive and dynamic when telling stories. He reached the conclusion that the genre had to abandon the language of words and focus on telling events.

At the same time, one of Leacock’s obsessions was finding the way to film with quality synchronized sound without the obstacles of cables and heavy recording equipment, and which would allow him move the camera freely. His last work, Toby and the Tall Corn, was followed by several «disastrous» projects in search of that freedom, including the curious Bullfight in Malaga (1959), in association with Robert Drew, with the guest star Ernest Hemingway as the protector of the bullfighter Antonio Ordóñez, which narrates the close relationship he had with master Luis Miguel Dominguín; which took place at a city in Andalucia in 1959.

A year later, Drew, who had founded Drew Associated and formed a spectacular group of work putting together D.A. Pennebaker, Terence MaCartney-Filgate, Albert Maysles and Richard Leacock, found the money to set in motion an idea Leacock had been thinking on since the filming of Jazz Dance. Why not put a quartz watch in the camera and an identical one on the recorder to get the synchronicity between both devices? They went for it and it worked; and finally the camera was liberated of cables and tripodes. It wouldn’t be long until the opening of the new genre Direct Cinema, also known as Cinéma Vérité.

The first production and maybe the most important fruit of Drew’s team was Primary (1960), a documentary about the primary elections in Wisconsin between J.F. Kennedy and Hubert Humphrey to decide who would be the democratic candidate for the presidency of the country. Drew had chosen young senator J.F. Kennedy, who wasn’t the favourite on these elections, for his first “production” and took a plane with Leacock to explain him what this new way of making documentaries was about and try to convince him to let them, him and his team, film his life from dawn til dusk during the campaign. Kennedy asked how this “experiment” was going to work, how were they going to show him in the final cut. Drew only said they would be impartial, since the idea wa to also film his opponent, and that he should be trusted. Kennedy’s answer was: «If I don’t call you by tomorrow, we’re on». He didn’t call.

They reached the same agreement with Hubert Humphrey and Drew and Leacock filmed both candidates for five straight days. The divided the job amongst the camera operators Al Maysles, Terence MaCartney-Filgate and Bill Knoll. D.A. Pennebaker joined them as well for the last night of the campaign. It was the first time a movie showed politicians like that, in the clamour of the campaign and also mixing with their confidants and family members in a way it made them forget there was a camera crew with them.

The documentary received the Robert Flaherty Award and the Blue Ribbon at the American Film Festival, but wasn’t very succesful in the States, where the TV companies refused to broadcast it because even though «You’ve got some nice footage there, Bob», it was missing a narrative voice. However it was received with eagerness in France because of its technologic innovation and the risky narration, which brought in a great revolution on the filming and editing techniques all over the world. In 1990 it was included to the American Congress’s Library as a film of historic importance.

«It is a great dream, the dream to become the president of the United States and it had never been catched by the cameras before»

[vimeo id=118834975]

Trailer of Primary (1960), courtesy of Drew Associates

Leacock and Drew’s joined work would result on several projects that were imitated all over the world. The freedom to follow the characters, no matter what happened, opened a new world of narrative possibilities. But the normal limitations within a production, the filming logistics, film rolls, batteries and such, seemed to be getting some new ones, on the one hand the shy support of the TV industry – Primary was eventually broadcasted on Time Life Broadcast – and on the other, the foreseeable lost of the character’s innocence in front of the cameras.

In 1963, the governor of the Alabama Estate, George Wallace, refused to comply with an order from the Supreme Court which forced him to allow access to the universities to black citizens. The crisis that arose between the governor and the country’s presidency was filmed by Drew and Leacock, whose team was joined by another camera operator, Gregory Shuker, and they were clever enough to obtain a permit from the governor to place a camera in his office.

A bit earlier, Drew had suggested the now president, J.F. Kennedy, to film inside the White House the real job of a President of the United States for the first time in history. Kennedy, who immediately saw the future value of that document, answered: «Yes-what if I could see what went on in the White House during the 24 hours before Roosevelt declared war on Japan?». The president had asked Drew and his team to run some tests to see if he would be able to forget about the cameras and do his job. And it work, to the extreme that a general had to remind him at some point that the cameras were filming while they discussed the issue of the military operations in Cuba.

Even though they were only tests, Drew turned them into a special for ABC channel. They now had the chance to film on a real crisis, between the president and governor Wallace. The film shows the strategy of Kennedy’s cabinet to convince Wallace, as well as the confrontation of the later with the State’s Attorney, who finally had to resort to the National Guard to make the governor give up on his decision and allow the access of the black students to the university. Crisis (1963) had a great impact on the American society and became a document of great value on the civil rights movement. Since then, it can be considered that the American political class lost its innocence and became aware of the power of documentary cinema.

Drew had the opportunity to shoot a third film about Kennedy, or actually about the survivors after the Dallas attack. Faces of November (1964), showed the reactions on the faces of those who attended the president’s funeral. The movie received two awards at the Venice Film Festival and meant a macabre ending for a trilogy that had changed the way of observing, filming and narrating. Even so, the revolution on documentaries, on cinema, was on motion.

Here come the French intellectuals

When Leacock and Drew presented Primary at the Cinémathèque Française, Henri Langloise, one of the founders of the institution, said about the film that it was «maybe, the most important documentary since the Lumière brothers». Without a doubt, Leacock felt happy about this affirmation because it represented one more big step to his final goal of managing to transmit «the feeling of being there», plus the recognition that the heirs of the inventors of cinema gave to Drew’s team’s great work.

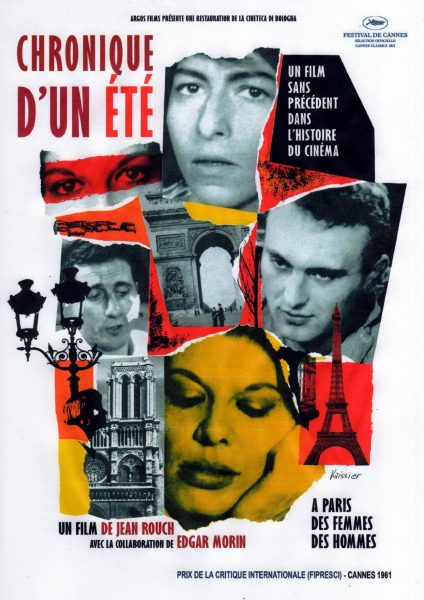

In 1961, French ethnographer Jean Rouch, who had already directed several documentaries, shot a movie using the lightest equipment at the time, the 16mm KMT camera and the portable magnetophone Nagra. Accompanied by the sociologist Edgar Morin and the technician and camera operator Michel Brault, he found himself on the streets of Paris and Saint Tropez asking people: «Are you happy?». The movie, Chronique d’un été (1961), that starts with an argument between Rouch and Morin on the possibility of acting sincerely and naturally in front of a camera, it was meant to be a study on the French society letting the interviewed people express themselves freely and genuinely before the camera. Following the suggestion of the movie’s publicist, the genre was given by Rouch the name of Cinema Vérité.

It seemed like the Americans – even though Leacock and Filgate were British – and the French – even though Brault was Canadian – had reached the same point almost at the same time, like on so many other occasions in the history of cinema. With less flourishes and intellectual pretensions, Leacock and his company were not only experimenting with new ways of cinematographic language but also figuring out how far they could go, shoving the camera into any environment that allowed them to portrait the contemporaneity, from underground movements, mobilizations pro civil rights, portraits of movie and music stars, to maybe the riskiest of subjects, the close examination of the political power.

Dziga Vértov’s old dream of the eye-cinema, of placing a camera as the witness of the come about of the society seemed to have been accomplished. From that point on, Direct Cinema and Cinema Vérité became synonyms. And the relationship between the French intellectuals and the more common, but just as efficient, American film-makers would continue to give results, but not always.

After an initial period in Drew’s team, in 1963 the society Leacock Pennebaker Inc. was formed, where both directors-operators would collaborate on another handful of essential films, now also as producers. Amongst others, they worked together on Happy Mother’s Day (1963) of which they made their own version, rejected by the tv channel that had hired them; A Stravinsky Portrait (1965), Monterey Pop (1966) and maybe the best known of all, Don’t Look Back (1967) considered one of the best documentaries of all times; about Bob Dylan’s tour around England in 1965, which opens with the classic scene of Dylan in an alley flipping through hand written banners with the lyrics of Subterranean Homesick Blues, and with the cameo of poet Allen Ginsberg, chatting in a corner.

«His words are ambiguous, his style is changeable, but he’s still the most influential voice of our time»

In 1968, Leacock and Pennebaker thought it would be a good idea to invite one of the fathers of the Nouvelle Vague, Jean-Luc Godard, to make a movie in New York. They had distributed, rather successfully, his movie La Chinoise (1967) in the United States and they offered him a project for what will end up being the PBS, the public TV station. The idea was to make a movie that would combine documentary scenes with some dramatized parts. Godard, who had already manifested that the United States where in the centre of the real cinematic and political revolution, seemed to be more interested on the metaphysical and mythological aspects of that alleged revolution than on the everyday work dealt with by his producers-camera operators. So seeing what things were like, Godard abandoned the project, honoring the expression “taking the French leave”, leaving the Leacock Pennebaker Inc. company with a financial debt that took them to bankruptcy.

We don’t know everything Leacock told journalist Richard Brody about Godard in that soiree at his house in Paris. What we do know is what he wrote about the whole business: «the Industry didn’t give a damn- after all the success with Primary, Crisis and other works -. The French intellectual film buffs did for a while but then came Jean Luc Godard and other obscurantists with heavy Marxist hangovers». End of quote.

That project should have been called, according to the French director, One A.M. (One American Movie) but Pennebaker ended up calling it One P.M. (On Parallel Movie) and Godard, sarcastically, hinted that could also mean One Pennebaker Movie. The thing is that Pennebaker didn’t finish his version, with the material filmed until the moment it was abandoned, until much later. Even today it is quite difficult to see the final result, but there’s a sequence that was almost saved from oblivion. It was the performance by Jefferson Airplane on the roof of the Shuler hotel in New York – The Beatles did it the next year, even though they are considered the first to do it – which has been imitated by several groups since. The filming took place from Leacock and Pennebaker’s office window in Manhattan, where Godard can be seen filming and giving directions.

«Jefferson Airplane performing for the first time on the roof of a building, commotion in the street, the police arrives, three moviemakers filming everything»

Where is cinema moving towards?

As time went by, Leacock’s skeptical gaze on the future of cinema intensified. In the 1950s he thought television would be the solution for those moviemakers that were trying to offer a version of reality different to Hollywood’s dream machine’s.He recognized that most of his movies had never been shown on TV – even to be able to watch Canary Bananas in the Canary Islands we had to wait until the homage they offered him at Guia in 2011 – and he remembered the experience with one of the most successful and well known documentaries he filmed with Pennebaker, Monterey Pop (1966). That film was an assignment from a TV channel, whose executives, when they watched the final version told Leacock and Pennebaker it didn’t reach television’s standards, to which Leacock replied: «I didn’t even know you had them». According to him it was the best thing that could have happened, the documentary was shown in the theatres with a great success amongst the audience.

«Janis Joplin, The Animals, The Who, Otis Redding, Jimi Hendrix… but it didn’t reach television’s standards»

Even though he recognizes he had only ever earned money teaching classes, not making cinema, his passion to grab a camera and just film never slowed down, even after the let-down with the cinema industry, that had chosen some time ago the path of big shows and big benefits in detriment of those stories that aspired to film on a small fragment of reality. He got excited when telling that other anecdote about his admired Robert Flaherty and his documentary Nanook, the eskimo (1922), that had to be projected, by orders of the distributors, accompanied by a movie by Harold Lloyd. The audience, according to the distributors-exhibitors, would ask themselves where the hero was, who was the heroine, what star was in it, it wouldn’t work on its own. However, Nanook became the first documentary to become a hit in the box offices.

In 1968, Leacock was invited to give a class at the recently created film school of MIT. In there he developed the filming techniques with much lighter and cheaper equipment, first with the versatile Super 8 and, years later, with the new video technology. For the next twenty years he directed and photographed several documentaries experimenting with the new technologies around him and always aware of what was happening before his eyes, like on the trip to New Orleans where he heard through some friends about the Queen of Mardi Gras celebration and, of course, he decided to shoot Queen of Apollo (1970) improvised, with his daughter Elspeth recording the sound. Before retiring from his position as a professor at the MIT in 1988, he shot one last featured documentary, Lulu in Berlin (1984), about the movie star from the twenties and thirties, Louise Brooks, who had one of those lives worth of a movie – as we can see -, but who was almost forgotten for years and, of course, recovered and honored in the fifties by the Cinémathèque Française. The documentary is a long and interesting conversation between Brooks and Leacock, where they go through the actress’ biography and the history of cinema.

«When she went back to the United States she was in Hollywood’s black list, she ever worked as an actress again»

At a moment during the interview, Leacock tells her: «…about the destruction of the people by the Studio System. I know it’s my own paranoia but you once said something very interesting about this…». Brooks continued: «Power is what they are after. Producers only search for power through money and sleeping with pretty women».

The title for the documentary makes reference to one of the movies she filmed during her European period, Pandora’s Box (1929), directed by Georg Wilhem Pabst in Germany. She had also worked in France with rather success and scandal due to the sexual content if those movies, including Pabst’s. She became a myth in Europe but when she returned to Hollywood they had forgotten about her. Brooks died a year after shooting the documentary. The BBC will dedicate her another one the following year, also with Leacock’s participation.

In 1989, Leacock settled in Paris for good with his third wife, Valérie Lalonde, with whom he also created a work team, producing the longest tape ever recorded with the Video-8 format, Ouefs a la Coque (1991), 84 minutes long.

«Life? Those little moments I want to share with people like me, not millions, but maybe thousands»

Richard wasn’t the only movie maker in his family, his older brother, Philip, was also director, and some of his children also worked in cinema. In 1941 he had married Eleanor Burke, daughter of philosopher Kenneth Burke, who was one of the pioneers in field ethnography. They had four children together: Elspeth, Robert, David and Claudia. Robert is a photography director in the United States.

His second marriage was to Marilyn Pedersen West, painter, writer and model, also a civil rights advocate. They had a daughter, Victoria, who is currently working as a film director as well.

Up until his last days, Leacock kept producing movies with his wife, Valerie, experimenting with new video formats that fascinated him with their high image and sound quality and their economy and ductility; far away from the canons and budgets of the big cinema and television industry. His last cinematic job was carried on in collaboration with his daughter Victoria in 1996, A Musical Adventure in Siberia (1996).

«I received a phone call from Russia. Sarah Caldwel was going to conduct a symphony by Prokofiev, never performed before because it had been forbidden by Stalin… can you do something?»

He left several writings about his great teacher, Robert Flaherty, about the new media and the new video formats and his particular idea of what making movies meant, which he summarized like this: «I’ve spent all my life observing. I love beautiful women, beautiful places, people’s reactions, the mystery of how they connect. I don’t want to tell people what to do. I’d rather observe, listen and film wonderful things, to put the together afterwards at editing and to try and obtaining the feeling of being there».

Leacock died the 23rd March 2011 while he was working on another idea, multimedia, that would compile his memoirs, writings, lessons and works throughout his whole career. The title he chose for this project was, of course, The Feeling of Being There. The memory of Canary Bananas, which he had conceived at that boarding school in London, almost eighty years earlier, with the intention of telling what his «Garden of Eden was like», would stay in his mind until the last moment.

Mostrar comentarios (0)