The Canarian Museum

We arrive at the Canarian Museum with our eyes wide open, with the intention of getting closer to that part of our past that has never been told properly, or actually, has never been understood. Because it has indeed being told by many researchers, historians, archeologists, naturalists. It is about that mythical and magical part of History, the most enigmatic piece of the Islands’ past, the lives of the men and women who lived here before the conquistadors arrived. The same people whose remains we can contemplate at the Museum’s glass cabinets while the experts explain us what it is they are doing to unveil their mysteries: who were they? How did they live and die? What was the reason for their funerary traditions? The How and the Why of the mummification. We listen to them as when, for the first time at the playground, we heard about how the Three Wise Men don’t really come from the far East. Fascinated by what the specialists in charge tell us about it, a group of scientists who, even after having overcome every inconvenience and obstacle thrown at them, they stubbornly continue the work that used to be a visionary’s dream.

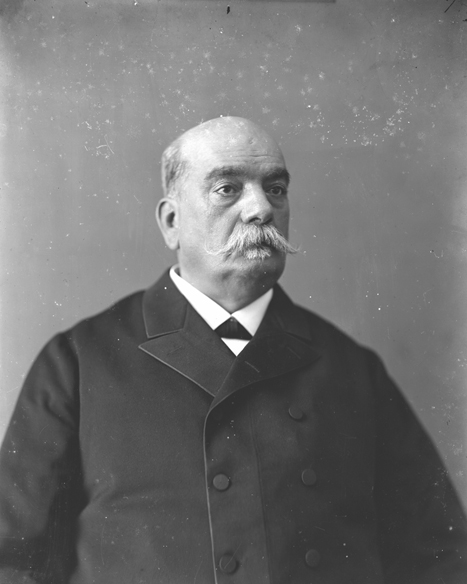

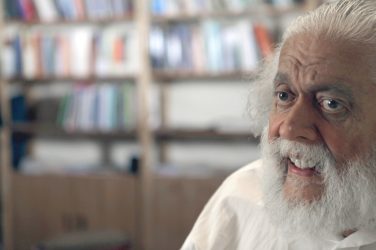

When Gregorio Chil y Naranjo, a seventeen years old boy from Telde in Gran Canaria, moved away to Europe with a suitcase under his arm and the wish to start his studies on medicine, he would have never been able to foresee what was waiting for him there. A personal and professional revolution will make him become Doctor Chil and decide to take on the boat back home, in that same suitcase, the project to create the Canarian Museum.

It wasn’t just a random destination in a random year. In 1848 Paris was burning. On February, a few moths before his arrival, the Second Republic had been proclaimed. That was the first of the many historical events he would experience first hand throughout his university experience. Those first impressions will remain carved into his mind forever. Many emotions for a teenager with a soul thirsty for knowledge, who came from a city with a population of under fifteen thousand people and a high level of illiteracy, and who’d just arrived to the place he’ll admire for the rest of his days. That feeling of freedom that could be felt all over the City of Lights will soon soak into the young man who years later would say: “A month after I moved to Paris I improved in such way that I became one of the most frenzied republicans”.

We can imagine him planning future trips on the brand new train, from the fabulous Saint-Lazare station, of which the impressionist painter Claude Monet would capture the smoke of the first train engines and the buzz of the travelers. Taking part on the famous games of chess at the Regence cafe. Chatting at one of its tables, far away from the crowd, with his good friend and future librarian at the Museum, Juan Padilla y Padilla. Next to other tables where Flaubert thought of Bovary and Honoré Balzac counted the last seconds before leaving for Saint Petersburg. While Alexander Dumas might invite them to a party and Victor Hugo was fighting with the first lines of Les Miserables. The two friends from the Canary Islands together in that adventure. Perhaps setting down the bases for their future project. Chatting and joking about the random encounter so far from their homeland, so different. Making jokes with their other friends from the Islands, Víctor Pérez from La Palma, key promoter of the botanic studies on the Islands, and Germán Álvarez.

For the nine years he lived in the French capital, doctor Chil y Naranjo has the chance to rub shoulders with the scientific elite at the time and will soon find out his passion for man’s natural history thanks to one of his professors and father of the Anthropology French Association, Paul Brocca. From that meeting the idea of dedicating a great part of his time and his finances to the study of the culture of the natives in the Canary Islands was born.

Finally he sets in motion the Scientific Society of the Canarian Museum in 1879, years after his return to Gran Canaria, together with other distinguished characters from the island such as Agustín Millares Torres, Domingo J. Navarro Pastrana, Juan de León y Castillo y Felipe Massieu y Matos. A year later, on the first floor of the Casas Consistoriales on Saint Ana Square, the institution is set up. This was a first for those first few local visitors since, up to that moment, the chance of getting close to the history of our ancestors was limited to the private collections of the island’s middle class. After his death in 1901, the Canarian Museum will have its headquarters in what used to be his home at Doctor Verneau Street.

“I admire Paris because Paris admires everyone. Paris is a real volcano that’s at a constant boiling point” Doctor Chil said once. That admiration will end up going both ways because it was also the French’s help, from the National Centre of Scientific Investigations, which will push forward the base again with a group of new local researchers and will open new tracks on the studies of the prehistory in the Canary Islands.

We are back to the twenty-first century and we visit the institution to learn about the job that started in 1880 with doctor Chil y Naranjo and to find out not only that this task continues with the same enthusiasm but also that they have now, in our opinion, a much more complicated mission.

Now the technic advances so fast we miss it during our twenty-four hours here, we realize we’d rather ignore it sometimes. Specially, like in this case, if it affects that image we had of the indigenous culture. We would like to keep our pre-historical and, maybe for some of us, necessary dream.

Doctor and curator at the Canarian Museum, Teresa Delgado, suggests us pointblank a radical change of perspective. Science and the new tools of study it has access to leaves us no room for doubts and, essentially, brings a change within the core of our being. She knows what she’s talking about and it makes us think she’s also aware of the effect of her words. On that moment, listening to her explanations on the last investigations and their conclusions, we feel the need to hold the hand that first took us to see the mummies again, to feel the arms that lifted us up to see them closely and woke up our passion to look into that mystery which is the pre-Hispanic history of the Canary Islands. A mystery learnt at school where they taught us, just by not doing it, we should ask the questions ourselves like others did before us. Those questions that ended up creating theories that, a long time ago, brought by scholars from all over Europe looking for tall, blond and blue eyed natives. That superior race that inhabited the mythical Atlantis.

Whenever we think of mummification our mind travels to Chile and its black and red wrapped up mummies, China or Egypt. We think again of the headlines over the probably last and spectacular discovery that was Nefertiti’s tomb. We can’t help thinking of a furtive connection that might have crossed the over four thousand kilometers that separate these islands form the Nile. During the pre-Hispanic period we are concerned about there are many theories about the arrival of the first natives to the Canary Islands. One of those theories, by Sebastián Jiménez Sánchez, talks about two waves of population coming from the north of Africa. The first one, according to the historian, would live in caves and would bury their dead in them through the ritual of mummification. The second wouldn’t use this technique but would place the departed inside tumuli or cists. This hypothesis, that differentiates between the mummified and the not mummified, has been challenged after recent discoveries that took place at the Necropolis of Maspalomas in Gran Canaria. At that excavation most of the near a hundred and fifty people found would have been shrouded and, apparently, not mummified.

The placing of the corpses and the wrapping process reveals the similar post mortem treatment found in those not mummified found in Maspalomas and the mummies kept in the museum. This makes us rule out the theory that mummification was a practice exclusive to the indigenous nobility.

Furthermore, the investigations taken place on the dentures of corpses belonging to both groups, prove that there are no evidences of differences between their diets either. It seems like the scientists.

The renewal of the archeological techniques that are being applied on the site at Maspalomas brings us back to he rooms at the number 2 of Vernau Street to start a completely new journey. According to Delgado we must change our perspective and ask ourselves new questions. The first one makes us wonder about the origin of the mummies at the Canarian Museum which makes us travel back to the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century. It is during this period that most mummies at the Canarian Museum were discovered. During this period the discoveries of “canarian antiques” were considered as something exotic. That meant the middle-class of those years, based on the period of the discoveries that were made at the time (Neanderthal, Cro-Magnon), would launch themselves into looking for anthropological remains sometimes even if it wasn’t them who would actually dig up the evidences themselves. That can be explained through the movement of cultural historicism (the object found was used to explain a society) which won’t give then any importance to where the objects were found. Due to this disdain on the archeological places and even more to the danger it implied getting to those areas, the figure of the “enriscador” appeared. Those were locals who were sent out to pick up the objects found at the sites and are also the cause why the researchers at the Museum find it so difficult to catalogue the heritage. It is obvious neither the “enriscadors” nor the collectors had enough knowledge to do this job without altering the valuable information the sites had to offer. Many of the objects and corpses that were found only have an approximate location of their origin. Specialists are faced with the tedious task of having to rebuild History in two stops: the first one from the present to when the object was found; the second backwards from the moment it was found.

That was precisely the problem scientists found when studying the famous mummy number 8, the one that, according to the school trips, belong to Artemi Semidan.

According to the first Norman chronicles on the conquest of Gran Canaria, Artemi appears to be an important member of the island’s nobility even often referred to as a king. Those documents tell the encounter between the French-Norman soldiers and the warriors commanded by Artemi without giving any explanation about his death during battle. However some following chronicles they do talk about his death during the confrontation even though historians cannot understand why.

Artemi’s figure had grown big, according to some historians, due to his brave and intelligent defense of the island, called Canaria at the time, against the Norman invaders leaded by Jean de Bethencourth. This fact is what will give the island the name of Gran Canaria.

Staring at his mummy, number 8, through the glass, exposed in a case separated from the second floor, as if somehow he’s still leading the rest of the mummies in battle, that was a strange and moving experience. That mummy represented the spirit of the fight and rebelliousness from the side of our ancestors that would combat the other side, struggling to not lose their freedom.

Walking now amongst the mummies again, listening to how the scientists keep trying to discover their many secrets, a feeling of admiration and respect overcomes us and we remember that first moment of discovery.

The memory is blurry like the prehistory of the Canary Islands found in the books. In there the word “myth” jumps at us, bothering us with its constant need of highlighting at the end of the lecture the fact that what’s been told is as volatile as our well know fine sand. We also ask ourselves if this might be a dream wrapped in haze, because we also need to confront those books written in other languages, to find our own history between the lines written by he chroniclers of other countries. Then and now we stumble upon the different interpretations of the language of the citizens of the island made by the French in the fifteenth century. This makes us think that, if the French pens are used to emphasize Artemi’s position as “king”, it must have been due to that very human quality of trying to enhance the figure of the enemy to avoid the embarrassment of having been defeated by men armed with some “brown twigs”. Many were the tries of the Castilian troops to disembark in Canaria only achieving some barters with the locals at sea. Natives were interested on the iron brought by the sailors, hooks and spearheads while the latter were more interested on Drago’s blood, the legendary tree. The natives would never let them put a foot on their land. Just like it happened that one time, according to Le Canarien, when Pedro el Canario, captive translator, went with Artemis to tell those from Castilla they would give them fresh water and provisions. When the boat got closer to the shore the Canarians set up a trap and, according to these chronicles, kept throwing rocks to Bethencourt’s men who then decided to forget about conquering Canaria.

In the meantime mummy number 8 sleeps in the Canarian Museum. Calm, unaware of the Normand accent, the Genoese, Majorcan or Castilian. We can imagine this man wandering about, far from the world, maybe ignorant of the fact that the Atlantic of the fifth century was his great ally because it was full of dragons that were able to swallow a whole ship and the curiosity of those who gazed into the horizon eager to overcome, one day, the fear of exploring the fearful ocean. Mummy number 8 winks at us once more. He reminds us again that he was here once, that we might not know his name here at tamazight but it doesn’t matter. He’s there, behind that glass at the Canarian Museum, so we don´t forget there were people who would shroud their dead then. That, whether they were mummified, their enigmas still intoxicate the minds of the researchers both in our language and in so many others.

![]()

Photos Copyright El Museo Canario.

Mostrar comentarios (0)